Vincent Van Gogh Biography

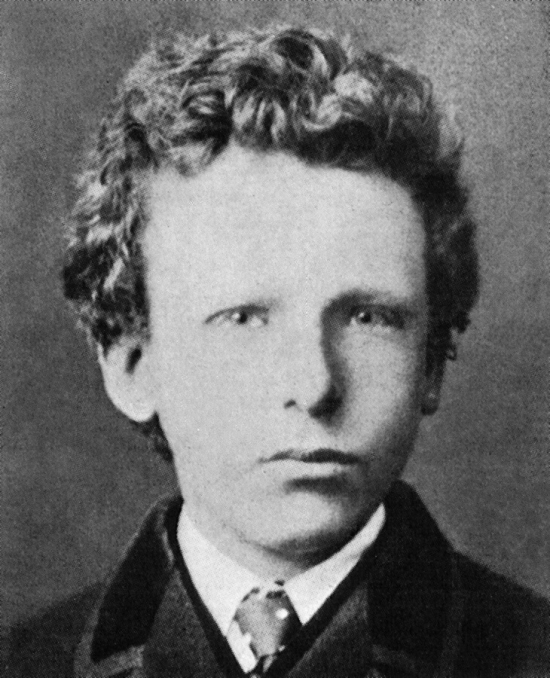

Yearly Years

Self-portrait with Straw Hat, 1887, Courtesy of The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, United States of America.

Perhaps more so than any other figure, the 19th-century Dutch painter and draftsman Vincent van Gogh has come to embody the myth of the tormented artist. Popular legends surrounding the artist’s life have become as or more famous as his artworks: that he was entirely self-taught, that he lived with a prostitute, that he cut his ear off for love, and that he shot himself out of depression. A closer examination of the artist’s life, in large part made possible thanks to extensive correspondence that has been preserved, reveals a far more complex figure than what is generally assumed.

During a career that lasted only around ten years, van Gogh produced over 2000 works of art, including drawings, watercolors, prints, and oil paintings. The claim that he only sold one of these works during his lifetime — The Red Vineyard, to the painter and collector Anna Boch — is likely to be more of a romantic myth than reality. We know that on a few occasions the artist received commissions for works (whose end results were not always well-received), and in other instances he traded works with his peers.

Toward the end of his life, van Gogh began to receive some recognition among art collectors and critics. Still, the success that he sought and worked so hard to achieve did not come while he was still alive.

Following his death, his fame grew steadily, and the impact of his work on subsequent generations of artists was enormous. In particular, he had a profound influence on the various strains of Expressionism that formed a crucial part of the art world in the 20th century.

Early Years

Vincent van Gogh was born on March 30, 1853, in the Brabant village of Zundert in the southern Netherlands, to Reverend Theodorus van Gogh and Anna Cornelia Carbentus. His father was a preacher in the Dutch Reformed Church, and his mother was the daughter of a bookseller. Four years later, in 1857, the couple had another child, Theo (Theodorus). The two brothers went on to form an extremely close lifelong relationship, much of which is documented in an extensive written correspondence.

Young Vincent began his formal education in 1860 at a village school in Zundert. He later transferred to a boarding school in Zevenbergen, where he completed his elementary schooling. As a young boy, he began making drawings, a practice that would continue throughout his life.

At the age of thirteen years old, Vincent started his studies at a secondary school in Tilburg. However, despite his good performance learning languages (French, English and German), van Gogh left school in March 1868 during the middle of the academic year. His formal education did not continue.

In July of 1869, thanks to his uncle Cent’s assistance, van Gogh began an apprenticeship at The Hague branch of the international art dealership Goupil & Cie (headquartered in Paris). Following his training, he was transferred to the London office on Southampton Street in 1873. During this period, he began collecting illustrations fromThe GraphicandIllustrated London Newsby artists such as Frank Holl, Hubert von Herkomer and Luke Fildes. The black-and-white illustrations of contemporary social problems in Britain had a profound effect on Vincent, and possibly contributed to both his religious fervor and his desire to later become a painter of peasants.

Although he had initial success working at Goupil & Cie, his performance began to deteriorate. In 1875 his uncle and father helped arrange his transfer to the company’s office in Paris. However, things did not improve, and he was eventually terminated from his position in late March of 1876.

Following his termination, he returned to live in England, where he found an unpaid assistant teacher position at a boys’ boarding school in Ramsgate, and later a paid job at a private school in Isleworth. This, however, was short-lived, and in 1877, following his father’s advice, he returned to the Netherlands.

His uncle Cent was instrumental once again to securing a job for Vincent working in a bookstore in Dordrecht, near Rotterdam. During this time, his religious fervor, which had been steadily increasing, grew strong enough that he decided to become a minister, and that year he moved to Amsterdam to begin studies in theology. Here he spent a year, where another uncle, a minister, helped him with his studies. But this was to no avail – lacking discipline to study, Vincent dropped out of school yet again.

The following year he moved to the poor coal-mining district of Borinage in southern Belgium, where he began working as a lay preacher. His extreme religious fanaticism, which led him to give away his possessions, sleep on straw, and live like a pauper, giving him the nickname “The Christ of the Coal Mine”, displeased the church. Due to this, in 1879, Van Gogh was dismissed from his post. The failure to find success as a preacher was a devastating blow to Vincent, yet it proved fortuitous for his art.

B.Schwarz, Theo Van Gogh, aged 15, 1873, Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Portrait of the Artist’s Mother, 1888, Courtesy of Norton Simon Museum of Art, Pasadena, California, United States of America.

Mid Years

In 1880, at the suggestion of his brother Theo, Vincent decided to devote himself fully to art. He had continued to make drawings and sketches since childhood, but this marked the beginning of a serious and lifelong pursuit to be an artist. In this period, van Gogh was particularly inspired by artists such as Jules Breton (1827-1906) and Jean-François Millet (1814-75), known for their images of peasants. Despite some aversion to a formal course of study, van Gogh moved to Brussels toward the end of the year to attend the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, where he studied life-drawing, anatomy and physiognomy. Theo, who had begun working for Goupil’s, began to support him financially at this point, so that Vincent could focus completely on his art.

Van Gogh continued his studies as an artist in the spring of 1881, when he moved to his parents’ home in the village of Etten, in the Netherlands. His course of self-instruction during this period involved collecting and drawing from prints and reproductions and studying from books. Partly due to his falling in love with his cousin Kee Vos-Stricker, who was a widow and was not interested in a relationship with Vincent, van Gogh’s relationship with his parents became increasingly strained. The problems came to a head in the winter of that year, when van Gogh left his parents’ house to move to The Hague, which was at that time the nucleus of the Dutch painting scene. Significantly, the move also marked the end of van Gogh’s religious fervor.

Fisherman’s Wife, 1883, Courtesy of Kroller-Muller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

In The Hague van Gogh began living with Clasina Maria “Sien” Hoornik, an abandoned mother from the lower classes who worked as an occasional prostitute, had a young daughter and was again pregnant. Both she and her family would serve as models for van Gogh during this time. Vincent’s parents and Theo disapproved of this relationship, and although he initially persisted, he ultimately decided to leave Sien.

In 1883, the artist left Sien and moved to Hoogeveen in the northern Netherlands. This decision was in part the result of a continued desire to be a painter of peasants. By this point he had begun producing independent works of art that were intended as finished pieces, rather than just sketches or studies.

After spending time living again with his parents, van Gogh moved to Antwerp in November of 1885. His father had passed away in the spring, a loss that deeply affected Vincent. His time in Antwerp was brief, and in February of 1886 he moved to Paris, where he shared an apartment with his brother Theo. In Paris, van Gogh came in contact with many other notable artists of the nineteenth century, including Claude Monet, Camille Pissarro, Émile Bernard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, and Paul Gauguin. Late in 1887, van Gogh arranged an exhibition for several of his artist friends and himself. The exhibition, held at theGrand-Bouillon Restaurant du Chaletin Paris’s Montmartre district, was notable for the first sales of several rising stars in the art world.

Woman (‘Sien’) seated near the stove, 1882, Courtesy of Kroller-Muller Museum, Otterlo, Netherlands

The Potato Eaters, 1885, Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

Later Years

The Church at Auvers-sur-Oise, 1890, Courtesy of Musee d’Orsay, Paris, France

Van Gogh’s final years, during which time his mental health deteriorated markedly, were spent in France. In 1888 he moved to a small town of Arles situated on the river Rhône in southern France, partly out of a desire to realize his earlier goal of being a peasant painter. He returned to many of the motifs of peasant life that he had worked on when he was living in the Netherlands: thatched roof cottages, fishing boats, a sower in a field. Many of his compositions from this period also reflect his fascination with the area’s landscape and light, and feature some of his most intense colors.

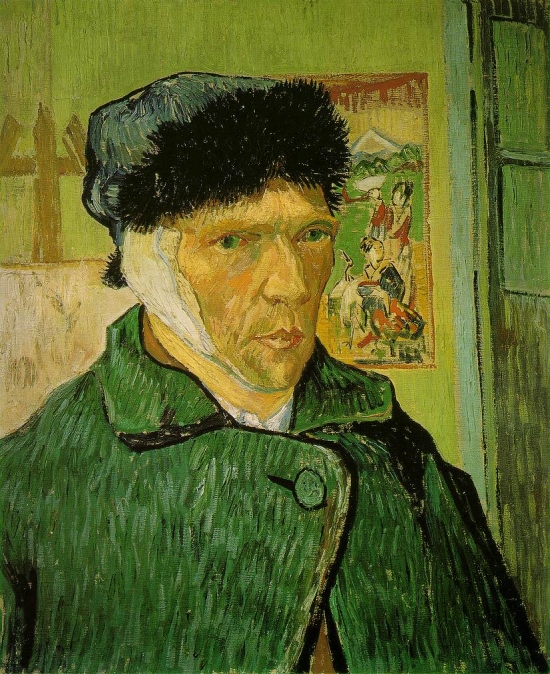

Van Gogh hoped to found an artists’ community in Arles, “A Studio of the South”, and eventually he succeeded in convincing Gauguin to live and work with him in the Yellow House, where he rented four rooms. Gauguin arrived in late October 1888. Working together, they produced some outstanding paintings. However, the two artists had frequent arguments, their arrangement was contentious and ultimately culminated in Gauguin leaving after only a couple of months, by Christmas of 1888. The events precipitating Gauguin’s departure included the famous incident of van Gogh cutting off his left ear and giving it to a prostitute, after which he spent several days in the hospital. He returned to the Yellow House following his hospital stay but was readmitted in February 1889 for several bouts of hallucinations and delusions.

In May of 1889 the artist committed himself to the Saint-Paul-de-Mausole Asylum in Saint-Rémy, due to his worsening mental health.

Theo managed to arrange for two cells in the hospital, so that van Gogh would be able to use one as his studio. During his stay, van Gogh continued to paint and draw when he felt well enough to do so. The hospital and gardens often provided subject matter, as did his own recollections. One of his most famous paintings—Starry Night—dates from this period.

Van Gogh left the Saint-Rémy clinic in May of 1890, having spent a year there. He moved to Auvers-sur-Oise in order to be closer to his brother Theo and the physician Dr Paul Gachet, who was treating van Gogh. This period saw the beginnings of critical success for van Gogh. Six of his painting were displayed in Brussells as part of the Belgian artists' association (“Les Vingt”) exhibition. Vincent’s work received positive feedback from art critic Albert Aurier, and most noteworthy was the sale of the paintingRed Vineyardto the painter and collector Anna Boch.

Soon after, during a visit to Theo, he discovered that his brother was planning to quit his job and set up his own business, which could potentially lead to financial difficulties. Unfortunately, van Gogh’s mental health continued to worsen due to these new financial worries and uncertainty about the future.

On July 27, he walked into a wheatfield and shot himself in the chest with a revolver. The wound was not immediately fatal, and van Gogh was able to walk back to the Auberge Ravoux, where he had been staying. When Theo heard of the shooting, he rushed to be at his brother’s side. In the early morning hours of July 29, van Gogh died from his wound. According to Theo, his final words were: “The sadness will last forever”.

Van Gogh was buried at Auvers, having left over 850 paintings and nearly 1300 works on paper.

The Bedroom, 1888, Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

The Starry Night, 1889, Courtesy of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, United States of America

Personal Life

Van Gogh’s personal life was often marked by turmoil, strained relationships and debilitating problems with mental health. Many of our insights into his thoughts, feelings and difficulties come via the extensive correspondence he maintained for much of his life, most notably with his brother Theo. Fragments of these letters were first published in the 1890s, not long after the artist’s death. As many of the artist’s letters contain his views on art and artistic principles as well as personal information, they were critical in solidifying van Gogh’s posthumous reputation and personality.

Apart from his lifelong attachment to Theo, Van Gogh’s familial relationships were often strained. In the summer of 1881, he developed an unhealthy obsession with his widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker, who refused the artist’s marriage proposal. The artist’s persistent efforts to court Kee resulted in significant quarrels with both her father as well as his own.

Arguments with his father were a contributing factor to van Gogh settling in The Hague in January of 1882. There he began living with Clasina Maria “Sien” Hoornik, a lower-class mother who worked as an occasional prostitute. Unsurprisingly, this arrangement did little to improve the artist’s relationship with his father. Van Gogh initially had plans to marry Sien, and she and her family served as the artist’s models during their time together. Ultimately, however, he decided to leave her and The Hague, partly out of a continued wish to become a peasant painter.

A.Greiner, Kee Vos and her son, 1881, Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

One of the artist’s more notable friendships was with the French Post-Impressionist painter Paul Gauguin, who met van Gogh in Paris in November of 1887.

The pair exchanged letters and paintings and had a brief living and working together arrangement during van Gogh’s stay in the Yellow House in Arles. But the artists’ personalities were often at odds, and this, combined with van Gogh’s erratic behavior, led to Gauguin leaving Arles around Christmas of 1888, after only two months. The living arrangement proved too difficult for Gauguin when, on December 23, van Gogh allegedly threatened him with a razor blade and then ran off to a local brothel. There he turned the blade on himself and cut off part of his left ear, which he then gave to a prostitute named Rachel. The artist was subsequently hospitalized, after which he made the decision to commit himself to an asylum for treatment.

Even before he was institutionalized following this incident, van Gogh suffered from bouts of mental instability. For decades scholars have offered theories on the specific affliction he suffered from. Suggestions have included schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, poisoning from the paints he used, epilepsy, and complications from the abuse of alcohol or absinthe. Despite the great deal of speculation, there is no consensus, and it is unlikely we will ever know for certain. It is also worth remembering that many of the diagnoses are modern terms and thus potentially anachronistic to apply to a 19th-century artist.

Ultimately, Theo was the artist’s faithful lifelong companion (even if their relationship was at times difficult, notably when they were living together in Paris). It was Theo who encouraged his brother to pursue art, who supported him financially, and who accompanied him during his final hours. Six months after Vincent’s death, Theo passed as well, on January 25, 1891. In 1914, Theo’s remains were moved from Utrecht in order for him to be lain next to those of his brother’s in Auvers-sur-Oise.

Paul Gauguin, The Painter of Sunflowers, 1888, Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

John Russell, Portrait of Vincent Van Gogh, 1886, Courtesy of Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam, Netherlands

How did Van Gogh really lose his ear?

Van Gogh, self -portrait with a bandaged ear, 1889, oil on canvas, The Courtauld Gallery, London

The story of van Gogh cutting off his own ear and then giving it to a prostitute is a widely known art historical legend. Yet unlike many legends this one is true. Scholars have long known that van Gogh, after an argument with Paul Gauguin on the evening of December 23, 1888, took a razor and cut off part of his left ear. He then wrapped the piece in some newspaper and gave it to a prostitute named Rachel. Following this episode, the artist was hospitalized and eventually decided to enter into an asylum for long-term treatment. In the wake of the incident Gauguin left the Yellow House in Arles, where the two had been living, never to return, although he and Vincent remained in contact.

That van Gogh’s ear was mutilated is certain: documentary sources as well as the artist’s paintings of himself with a bandaged ear attest to this fact. But recently two German scholars have questioned whether van Gogh is to blame. Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans, in their book Van Goghs Ohr: Paul Gauguin und der Pakt des Schweigens (“Van Gogh’s Ear, Paul Gauguin and the Pact of Silence,” Berlin: Osburg, 2008), argue that it was Gauguin who cut off van Gogh’s ear, doing so with a fencing sword during an argument. They base their claims on a variety of sources associated with the event, including police records, van Gogh’s own letters, and theories on the artist’s mental condition at the time.

According to Kaufmann and Wildegans’ theory, Gauguin and van Gogh were arguing over the prostitute Rachel and the best way to paint. When van Gogh became hysterical at Gauguin’s threatening to leave Arles, Gauguin brandished his fencing sword (he was an amateur fencer) and accidentally sliced off part of his friend’s ear. The two artists then hid the truth in their police statements, likely to protect Gauguin from prosecution.

To support their case, the authors point to inconsistencies in the police records and cryptic statements in the artists’ letters, although they admit their evidence is ultimately inconclusive. Most van Gogh scholars remain unconvinced, even if they find the theory interesting and recognize that Kaufmann and Wildegans have done an admirable job analyzing the documentary evidence. Ultimately the debate points to the continued interest in and fascination with van Gogh. Stories such as this one are a part of our cultural heritage, as much or more so as the artist’s paintings and drawings.